Humans have more often thought of what it would be like to be an animal. A philosopher called Thomas Nagel once wrote an essay about it: “What it’s like to be a bat”. In his opinion we will never be able to find out what it’s like to be someone or something with a different brain, because there are certain ways of looking at the world, or methods of perception, that we will never experience. We won’t know what it’s like to have sonar, or what it’s like to fly or anything like that. Even with our modern ways of measuring the brain, he argues, we will never know the real feeling.

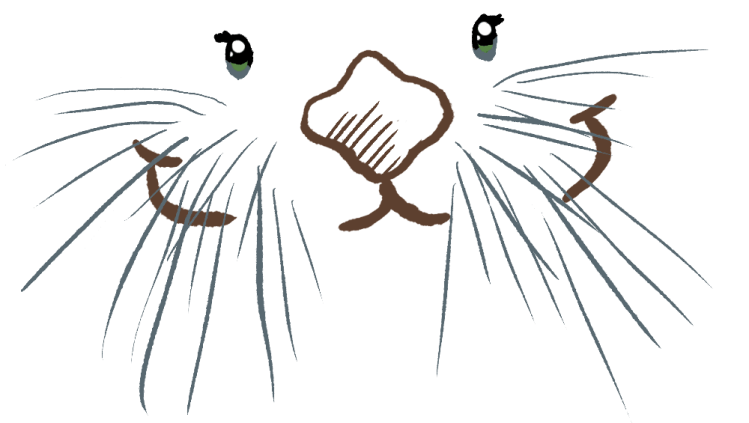

Take the whiskers of an otter for example. A typical otter has about a 120 of these strong, sensitive hairs on their muzzle. They are not like our normal everyday hairs, with which we sense touch and temperature. These things are supersensitive to currents, air, and touch. The beard and moustache have re-gained popularity in human males, their modern-day function remains, while fluffy and warm, mostly a fashion-statement and the otter mystacial (Merriam Webster: having a stripe or fringe of hairs suggestive of a moustache ) serves a different purpose.

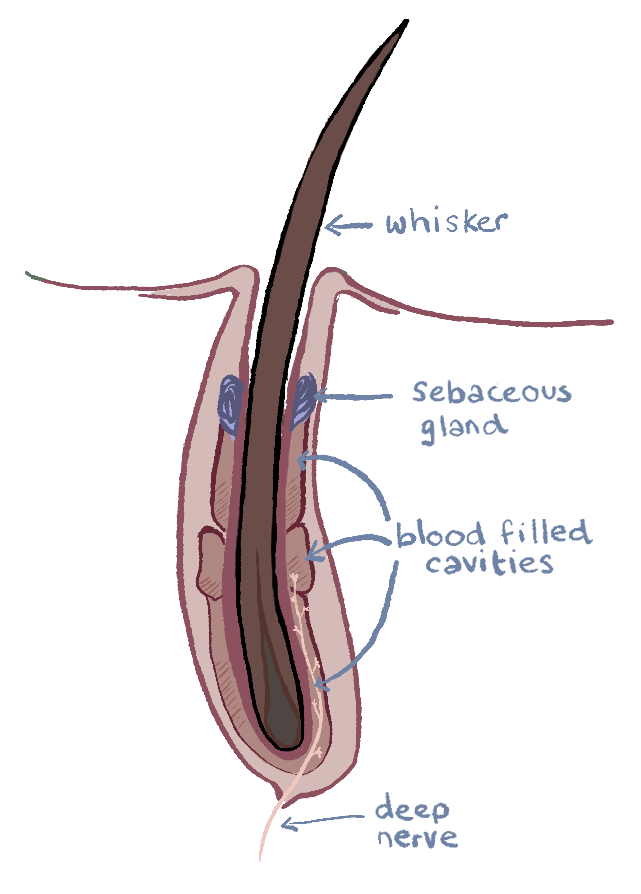

So how does Otter actually gain anything through whiskers? For that, we need to understand the detailed anatomy of the whisker and how it’s embedded into the muzzle. The root of the hair is surrounded by three blood-filled cavities, which are enclosed in a stiff capsule. In the top one cavity, you can find the sebaceous glands: This gland excretes oil to add an extra waterproof layer to the skin.

At the bottom of the entire capsule, a nerve enters. This nerve innervates the entire capsule, and takes all the sensory information from the whisker to the brain. So when the whisker is moved by wind, water or any other type of thing that causes motion in the cavities, this innervates the nerves and sends that information to the brain. Specifically the sensorimotor cortex of the brain. This is the part of the where sensory information from the environment is received and coordinated with outgoing motor actions. It is important that all this information travels and integrates swiftly, as an otter needs to respond quick and stealthy; hunting for fish and fleeing for bigger predators.

Therefore, all the sensory information coming from the whiskers should be relayed super fast! Luckily, the deep nerve brings information from about a 1339 myelinated axons per whisker! This makes the whisker very sensitive, and communication of tactile information very fast. A 120 of these whiskers inform Otter about everything happening around her…

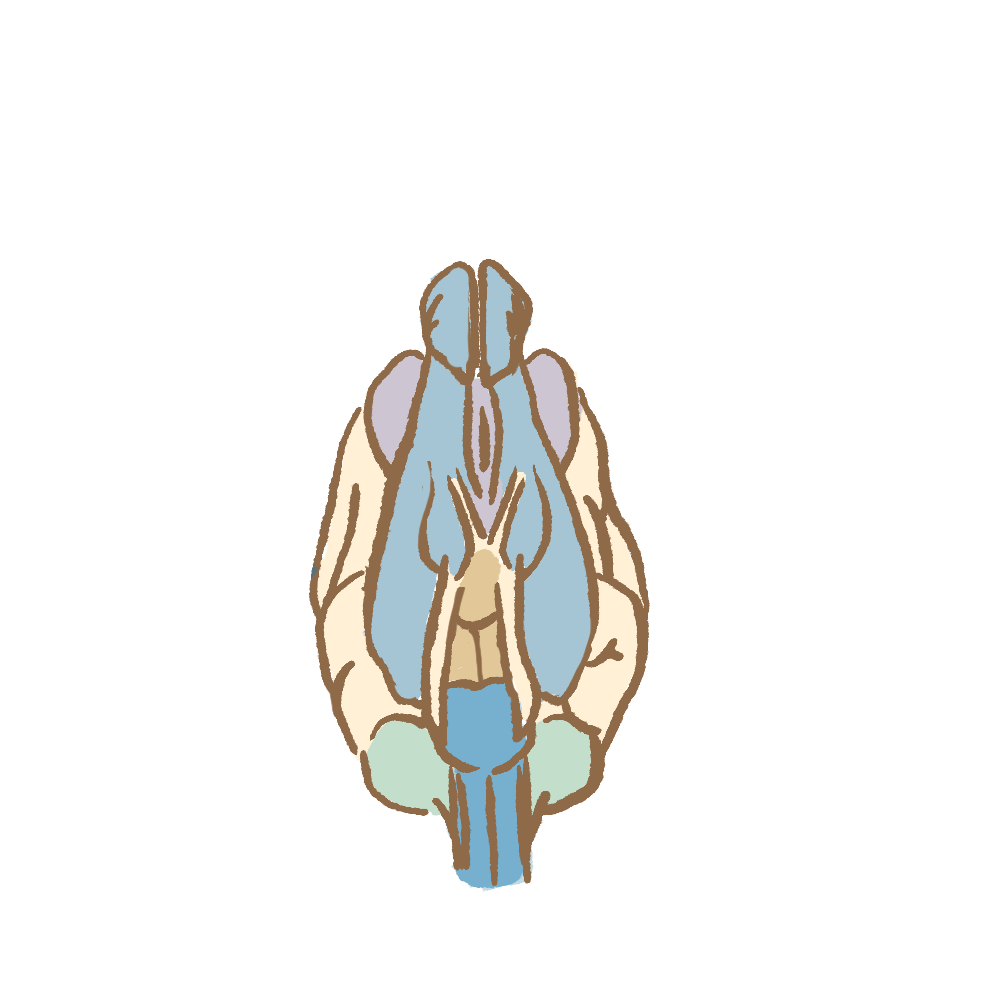

An Otter Brain

While Mr. Nagel has a point; We would have no clue what having whiskers would actually be like, humans are pretty good at simulating certain sensations that are characteristic for specific animals: like flying or locating other people using sounds, think of Marco Polo…

The brains of other animals are wired differently, to allow for things like sonar and whiskers. The evolution of different species’ way of living and environment has made sure that our brains are in sync with the body that we have. Therefore, we may be able to better understand some types of behaviour through looking at the brain, its’ shape and activity, and comparing this to our own.

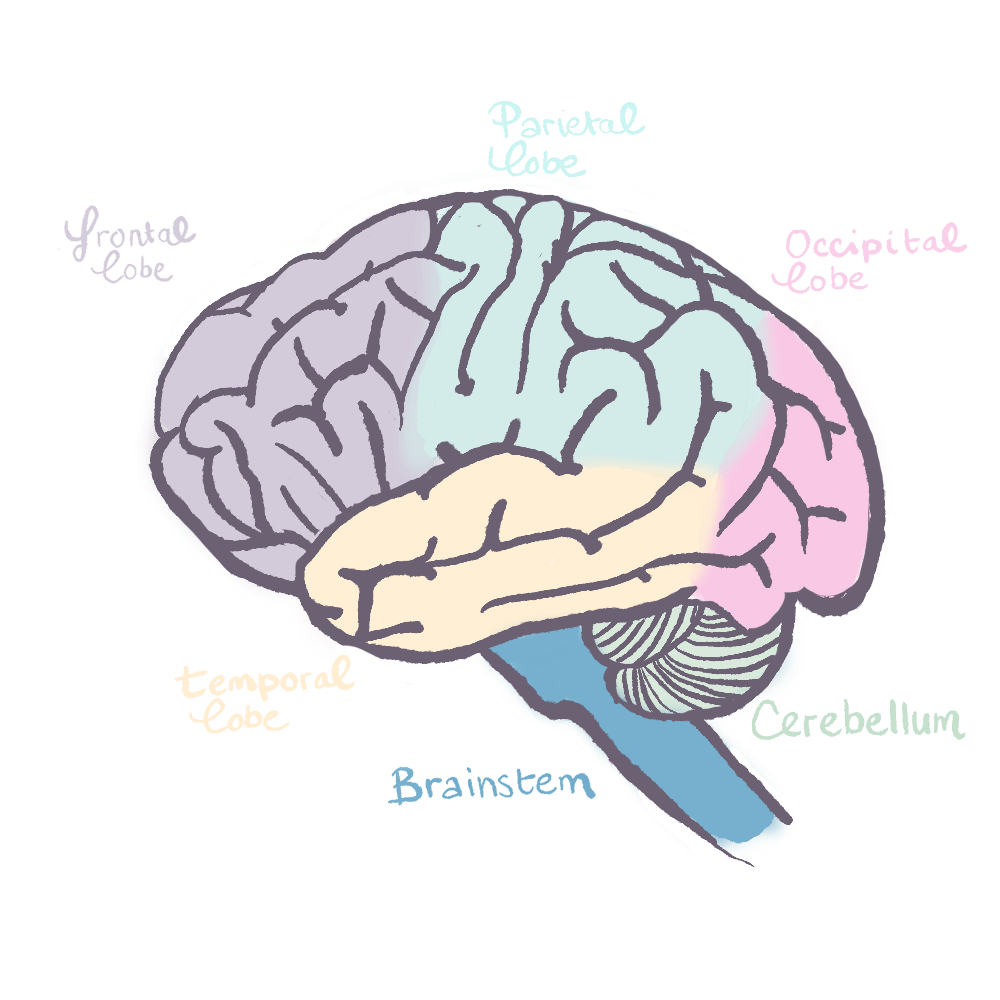

For example, we can compare brain regions with a similar function, in different species’ brains. These are called analogous regions: We can make assumptions about the size of a certain region, and the shape, and how it affects a species’ behaviour and perception of the world. While we will never know what it’s like to be an otter, we can try to imagine.. Let’s look at the brain of a human, and the brain of an otter. After foraging for any clues about the appearance of the otter brain online, I managed to find a very old veterinarian journal from the 70’s, with an article dedicated to exactly this!

Epic findings = epic day.

Looking at these, we see that we both have the same brain regions, but the first noticeable difference between the human and otter brain lies in size and shape. These illustrations won’t be exact representations of the brain and their ratio in size, I apologise. I imagine that the otter-brain is not much larger than a lemon, while the human brain is about 1200 cm3. We have a much larger brain, which is logical since our head is about four times as large. On top of this the Otters’ brain has a different shape. While the otter brain is quite elongated, the human brain is bulky and rounded.

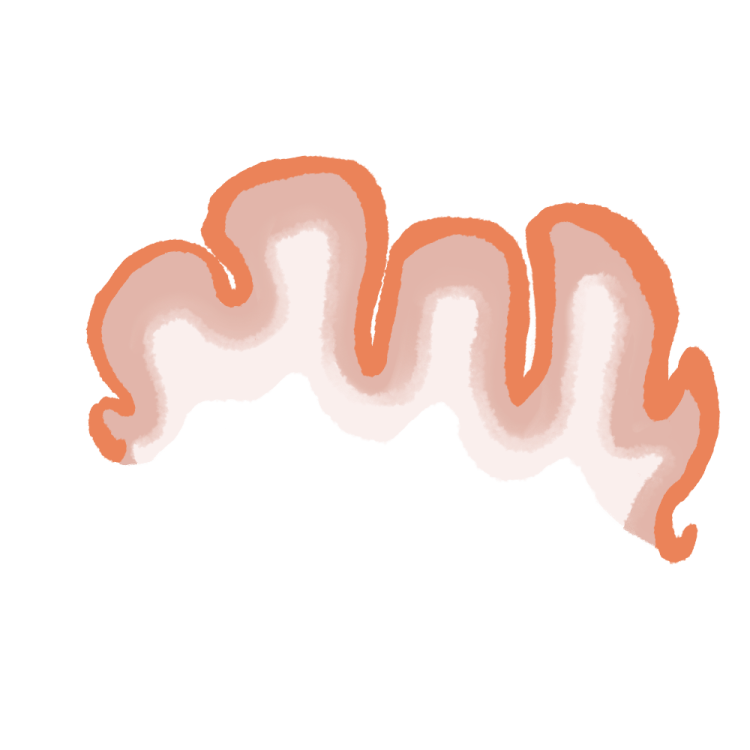

It’s important to keep in mind that we cannot deduce an animals level of intelligence by looking purely at the size of the brain. While it is more useful to look at the relative size compared to the size of the body, this is also not a direct indication of complex behaviour. The folding of the surface of the brain, called gyrification, is a better estimation as this indicates the surface area of the brain. However, there are many factors influencing intelligence and brain function, including the speed with which brain cells communicate and the relative size of certain brain regions.

The brain is such an intricate organ, and still contains many mysteries for us. That is why we still need to link brain to behaviour and see whether we can speculate on one, using the other!

The frontal lobe, which is important for executive functioning (things like attention and memory), is very developed in humans. This part is also called the “new brain”, an important feature that I will come back to later.

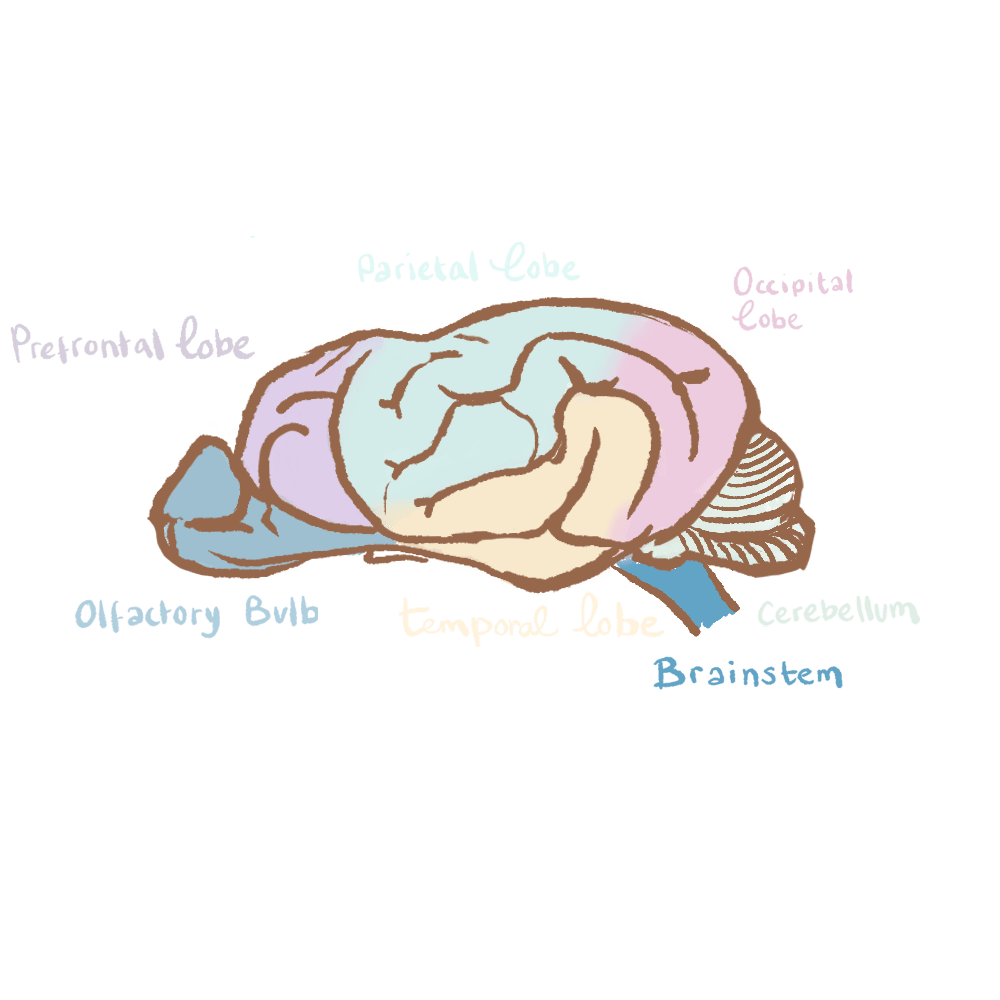

Another important observation is the size of the olfactory bulb. The olfactory bulb is the region of the brain where information of smell is received before it is further integrated in other brain areas. We, humans, barely have an olfactory bulb. The otters’ olfactory bulb is very large compared to the rest of the brain, and even sticks out at the front! This may suggest that the perception of an otter is highly influenced by smell.

The parietal lobe of the otter is quite developed. An indicator of this development may be the gyrification in that area. Especially the somatosensory cortex, a part of the parietal lobe where the information from the whiskers and the nose arrives! That makes sense doesn’t it? Some extra gyrification and more communication within the somatosensory cortex, may be an indicator for more intense processes going on in that region, which can be linked to the otter’s exceptional sense of smell and tactile abilities.

In Otter Words: By looking at the brain, the activity of the brain and certain behaviours of an animal and comparing it to others’, you can try to connect functioning to location. It is still a very mysterious topic, of course, because it is difficult to know what’s going on in their mind with certainty.

The Otter & Otters

Otters function nicely in social groups and sometimes even in cooperative hunting and problem solving. This is a trait that is also very rare in animals. We, humans, are considered to have developed this huge new part of the brain other animal-species don’t really have. This is because we can make a lot of social bonds. Being social, and having several social relationships is thought to be related to the size of the Prefrontal Cortex. This also happens to be the part of the brain that is important for “executive functioning”. Executive functioning sounds important, because it is. These are the skills you need to process information, and to act on it. Such as your memory, your attention, impulse control and organisational skills.

So otters are pretty social. River otters a little more so than sea otters. River otters also tend to look further than their own species to make friends. Like in this video, in which a river-otter longing for a belly-rub tries to make friends with a deer

So, better executive functioning may also lead to a bigger frontal lobe (or vice versa) and to the ability to retain more social relationships. You still see a much larger frontal lobe in humans, and I have the feeling that over the years this may develop more and more: Our social networks are growing larger. We are able to maintain contact with people that we met in far-away places, and people we met years and years ago, through social media. The amount of people we know and keep in touch with is astonishing, and I expect this to have great impact on our brain functioning.

Otters like to socialise, but on a different level than humans. River otters often hang out and hunt in groups, sticking around with mum. Sea otters go out to hunt on their own, but hang out together. They do this in single-sex groups, the floating sea otters together are called rafts. Lounging in their sea-rafts, otters also often grab each others hands to not drift off. All the while being adorable and social in this action, it also shows that otters use can cleverly adapt their environment in their advantage; They don’t only use each otter but also all the kelp they can find and wrap it around them to prevent drifting away from the raft out into the open sea

The Nifty Otter

The use of kelp shows that otters are one of the few species that, like humans, use tools. Even more importantly, tools or also used for hunting: Otters use rocks to bash open clams. You might never consider this, but intentionally grabbing one item, like a rock, that doesn’t seem particularly relevant to your immediate survival is not very logical. So the fact that otters are capable of making the in-between step to value something of indirect use to them, is very impressive!

“Hey, a rock! Epic, I can use that to open this clam I’ve been holding on to!”

If they happen to have a favourite rock, they can even store this, along with some food, under a flap of skin in their armpit.

How great is that? Imagine having an extra pouch underneath your armpit to hide your spork and snacks…

Anyway, the use of tools is considered highly innovative in the animal kingdom. We started doing this to transport stuff, to make a fire, to hunt, wage wars etc. before we grew out to be the species that conquered the entire planet.

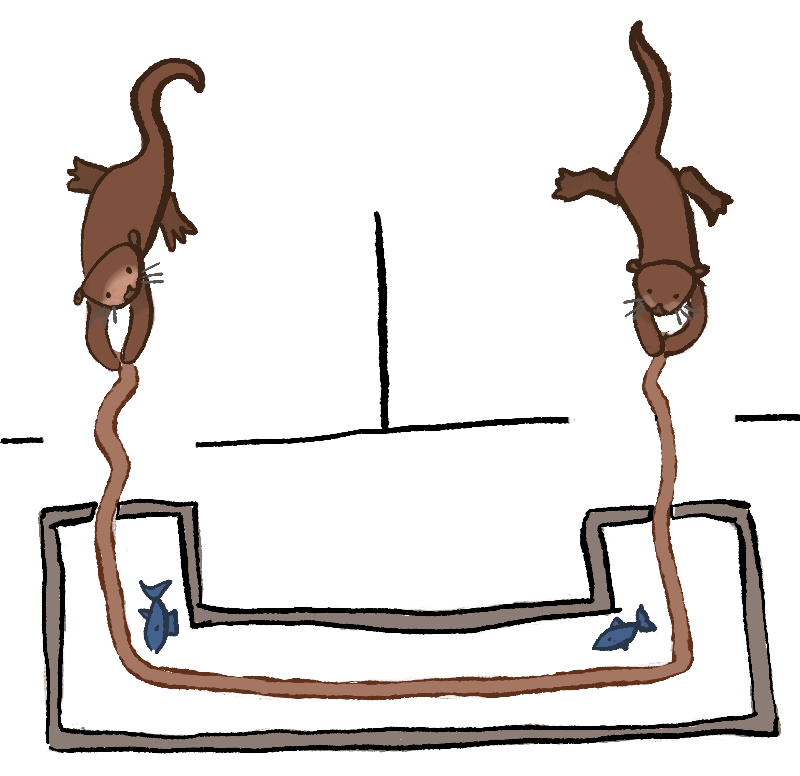

Another interesting task to test both an animal’s social and tool-using ability, is the “Loose-string-task”. Luckily for me, this was also done with river-otters. In the task the otters need to cooperate in order to get a treat, which in this case was a fish. The otters were taught to pull a string in order to haul in their reward. In the version where their cooperative capabilities are tested, an extra player comes in. The otters need to coordinate their actions: pull the rope simultaneously to haul in a prize for both of them. If one otter proceeds to pull the rope in a self-centered manner, the string will also be pulled out of reach for the other otter, making it impossible to retrieve any of the fishes.

This tests the ability of an otter to use a tool for a reward, like it does with the stone: “If I pull this rope, I will get a treat”, but it also requires them to take anothers’ perspective on a task: “This other guy also needs to pull the rope, and I need to pull only when I see he will do that too” . This perspective taking is brought to the next level in the delayed version of the task, in which one otter is allowed in the area where the rope is before the other otter is… This may cause issues with inhibition-management. As the pulling of the rope is already related to reward. The otter now needs to control the urge to already pull the rope, wait, and thereby realise that his otter-partner is essential in this task.

Both species of otters, the river and sea otter, were able to complete the task. However, they performed a lot worse in the delayed version of the task. This indicates that while they have the ability to coordinate their actions, they cannot inhibit their urge to pull the rope enough to coordinate with their partner. For these types of lab-based tasks it is important to consider the factors that influence the otters’ performance. Their environment is not their natural habitat, and the partner they cooperate with (although in this task usually part of their in-group or a sibling) may not be the otter they would want to cooperate with… All in all this shows that otters can use tools to gain rewards, and can even do this in cooperation, but not, however in higher level cooperated actions.

The Self & the Otter

Lastly, a component we consider important concerning an organism’s intelligence: Self awareness. How do you find out if an animal is self-aware? Psychologists have been doing this by placing a mirror in front of them and seeing their reaction. First, the researcher will just observe the animals’ behaviour.

Thereafter, the animal will be marked with some paint or dye or even a sticker, and is placed in front of the mirror again. If the animal starts behaving differently, paying specific attention to the mark on its body, you can assume that the animal is aware that they are the entity they are looking at in the mirror.

Sometimes, marking the animal is not even necessary, as the animal will portray “self-directed behaviour”. This is behaviour that the animal typically does not portray, but will now do in order to look at itself in ways it is usually never able to! These include things like opening their mouth, picking up stuff and presenting it to the mirror, as well as showing their bellies. As such, the animal uses the mirror as a tool to inspect itself.

Often, an animal will consider their mirror-image a different animal, and will respond either in an aggressive, curious or affectionate manner towards their reflection. With the mirror self-recognition test you can determine whether they do recognise themselves and realise this. So can otters recognise themselves in a mirror? We have seen that certain animals can, including dolphins, elephants, some great apes, and of course humans, but from about 18 months of age.

Unfortunately, I have found no proof that otters can. While there are videos of both a river-otter and an Asian sea-otter in front of a mirror, they don’t seem to portray self-directed behaviour… To be honest, I do believe that the otters will be able to pass the test if they are subjected to it. But that’s just speculation from my side, for now you can consider her a non-self-aware-tool-using mammal.

In Otter Words: We can be pretty clever, testing the waters with our whiskers, hiding our tools in our armpits, scheming with our squad. There’s still a lot you don’t know about us, but hey, there’s still a lot you don’t know about yourself either.

Let’s find out together!

Wanna check out some otterly academic sources?

Here ya go:

- Nagel, Thomas. 1974. “What Is It Like to Be a Bat?” The Philosophical Review 83 (4). (Oct., 1974), pp. 435-450. https://faculty.arts.ubc.ca/maydede/mind/Nagel_Whatisitliketobeabat.pdf

- Marshall, Christopher D., Kelly Rozas, Brian Kot, and Verena A. Gill. 2014. “Innervation Patterns of Sea Otter (Enhydra Lutris) Mystacial Follicle-Sinus Complexes.” Frontiers in Neuroanatomy 8 (October): 121.

- Hadziselimović, H., and F. Dilberović. 1977. “The Appearance of the Otter Brain.” Acta Anatomica 97 (4): 387–92.

- Schmelz, Martin, Shona Duguid, Manuel Bohn, and Christoph J. Völter. 2017. “Cooperative Problem Solving in Giant Otters (Pteronura Brasiliensis) and Asian Small-Clawed Otters (Aonyx Cinerea).” Animal Cognition 20 (6): 1107–14.

Hahah amazing stuff Joos! You had my curiosity, now you have my attention…

Thank you Joos,

it reminds me a bit of the opportunistic feline demeanour, in Otter words:

cats – who copied our whiskers – but just don’t like to be in the water.

I am looking forward to read your next blog

Hi Josie, I’m in Amsterdam next week (from tomorrow). I’m not sure if you are anywhere nearby but it would be great to see you if you are. Interesting blog. Glad to see you’re finding a way of combining your interests.

Hi Stephen! Such an amazing surprise to see your comment, thanks for reaching out! I’ve just send you an e-mail to your uca-mail. Unfortunately I’m out of the country until Thursday, but am afraid you won’t be in Amsterdam anymore this Friday?