On a More Personal Note

I am a middle child, raised between two very interesting brothers. The oldest one is highly intelligent. The youngest one is intellectually disabled. Since this post is titled Intellectual Disability, you might’ve guessed that I will be writing mostly about Mr. Younger Brother.

Perhaps, I’ll write about the elder too, one day, since he undoubtedly also has a fascinating brain.

The younger brother is 2 years my junior, and we happily grew up together. Back then, I never really grasped the fact that something had caused him to be “different”.

I did understand the fact that our parents payed him extra attention, as he needs more guidance in everyday life. I also paid extra attention to this myself, to take care of him and to make sure that he was content and safe. I also wanted to ensure that people around us understood the situation, and weren’t intimidated by something that might be odd for them. However, never before did I realise, the immense concern that my parents must have felt after he was born. That something was wrong with their newborn child, and that his health might be at risk.

While my parents had numerous hospital visits, scans, and other measurements we never received a diagnosis in the first 22 years of his life. Countless times a neurologist just could not tell them with certainty that there was indeed a developmental issue. Eventually, all the studies and examinations lead to the conclusion that he had probably suffered from oxygen deprivation in the womb. Based on the brain scans my parents were given “a diagnosis”.

Periventricular Leukomalacia

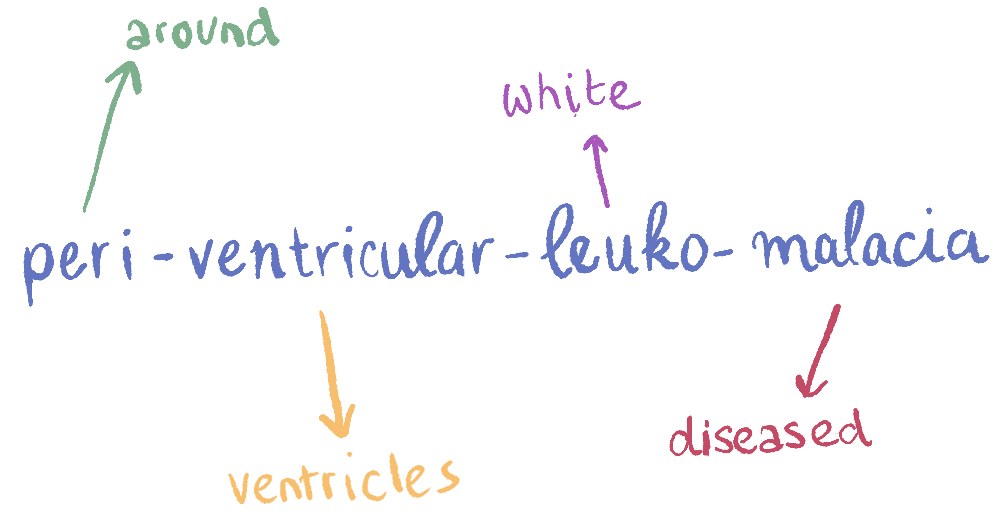

A superduper complicated word if you look at it like that.

So let’s tear it apart:

Peri means around and then there’s ventricular, which indicates the ventricles, the cavities of the brain, so something “around the ventricles”.

Leuko is white, and malacia means diseased.

Which comes down to: around the ventricles white diseased…

In Otter Words: There is something wrong with the white brain matter around the ventricles.

Cerebral palsy, damage to the brain, due to oxygen deprivation.

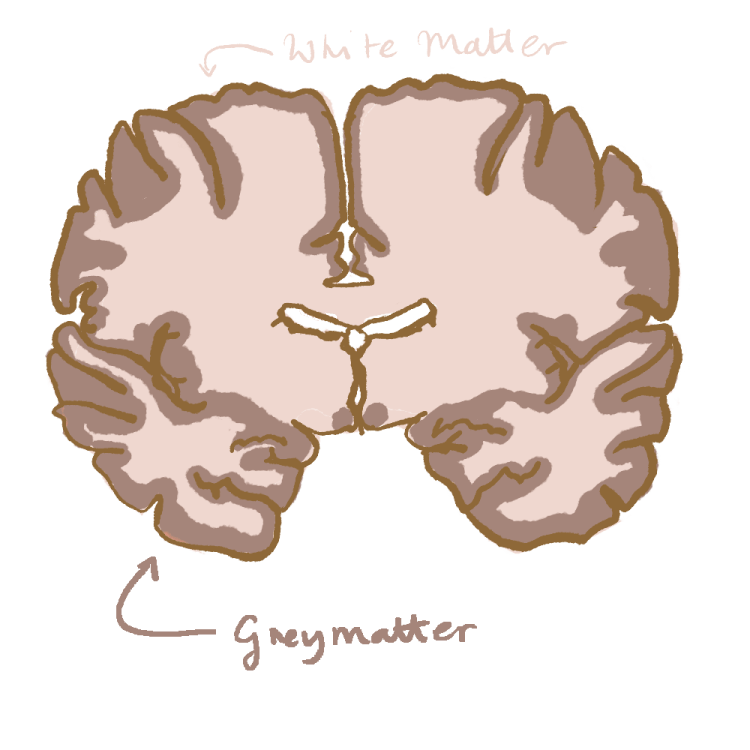

A brain’s grey matter is the darker outsides of the brain. You could compare it to the brain’s headquarters, as it is where all the cell bodies of the brain cells lie.

White matter is the big highway between brain regions. In earlier times, it was thought that white matter wasn’t very important, but it is a huge communicative relay within the brain!

The white matter is whiter than the rest of the brain because it contains al the myelinated axons. Axons are the part of a nerve cell through which messages are sent from the cell bodies. Myelin is a fatty substance that envelops the axon. The myelin sheath around an axon, makes transduction of electrical communication between nerve cells faster, and gives a white fatty colour.

So, periventricular leukomalacia: something was wrong with his white brain matter… In neurological terms a very, very general observation, as it actually did not give a real explanation of what actually was wrong.

Still, it sounded intricate and impressive. So, whenever someone asks me what my little brothers’ exact disability was, I would proudly recite the difficult word. Picture this: A 9 year old teeny tiny girl belting out…

“PERIVENTRICULAR LEUKOMALACIA!”

with a slight lisp.

This usually resulted in people looking a tad frightened. So then I just started to describe how my little brother was different from the norm:

He couldn’t speak, but he could walk. Even though at times it looks as if it might be a little difficult for him.

More precise controlled movements are more challenging, like those needed to pour yourself a glass of milk, or to use cutlery.

He drools sometimes, when he’s trying to focus, or when he’s not focusing at all…

He isn’t “potty trained”.

But he’s incredibly social, understands everything you say to him as long as it’s not too complicated for a 5-year old to understand. He is highly empathic, and feel emotions very strongly himself as well. He is able to play board games now, rolling the dice and already planning who he can kick off the board. He uses music to communicate his thoughts and feelings, navigating through Spotify to find the fitting song. Therefore, I believe he can count, and I believe he can read. Just not in the way that everyone else might have learned it.

For many, intellectual disability is a difficult topic to talk about. But I’d like you to know that I never experienced it as something sensitive, or as a touchy subject. My brother was of course not “something we did not talk about”. He brings our family to the next level; it teases out an open-mindedness and perseverance you need, when growing up in such a situation.

In Otter Words: I’d like to think that we could often learn a whole lot from individuals with Intellectual Disability. Of course, it is a limiting condition, that may affect your health and functioning, but I also feel like it offers a new perspective on goals in life. Rather than solely aiming for the highest level of education, job perspectives and such, you seek out health and happiness. Allowing you to value all the other extra bits that life is able to offer you, regardless of your limitations. Still, intellectual disability has an odd image in society.

The Image of Intellectual Disability

The cause of a disability can be something induced by ones’ environment, such as a traumatic injury, or something genetic. The nature nurture divide, if you will. In this section I will talk about the genetic cause of intellectual disability.

In earlier times it was not known that a disability could be a consequence of your genetic makeup, and therefore different reasons for someone’s defect were thought of:

It was something that was dealt to you by God, for instance, to teach you. It was the fault of the parents, or the medic at work. Early psychology even liked to blame a mother’s behaviour for a dysfunction of their child.

We are starting to understand the mechanisms behind these types of conditions. That there is no higher power casting a curse, and that it solves nothing to blame someone for it.

Genetic research is thriving. Scientists understand the composition of our genetic makeup, the way it is constructed, and the way it determines our phenotype. Consequently, it makes it possible to tell when something within our genetic makeup has “gone wrong”. It is therefore also now that new syndromic intellectual disabilities are being put on the map rapidly.

This is also why, a little over a year ago we finally received the real diagnosis for my brother’s disability. My parents had been called in again, and were informed that the genetic sequencing had been improved significantly since the last screenings. With this information came the question of whether we’d like to be checked again, as a family.

We agreed to participate in this new screening, as we thought it would rule out any genetic factor. We thought we could dismiss stressing about passing on “faulty genes” if I, or my older brother, would have kids one day.

It was all to rule out something genetic, but then my mum was called.

She was told that her son indeed had a genetic mutation. It was located on the so-called GATAD2B gene: an error in his genetic code had caused for him to be like this. At that point in time, he was the 100th diagnosis in the world and the 10th in the Netherlands. The syndrome had been described in Nijmegen, the Netherlands for the first time in 2013. Very close to home!

Only a month later we got introduced to an entire new group of people, who had faced similar challenges and joys as we had. One of their family members, their child or sibling had also had the GATAD2B mutation, and was diagnosed with GATAD2B Associated Neurodevelopmental Disorder, in short: GAND.

The Use of a Diagnosis

You always think your brother is unique; you resemble each other a bit as you are siblings – but his facial expression, the way he smiles, the way he looks and moves. That is something unique, right? Imagine finding out that he has a type of syndromic intellectual disability that does not only cause cognitive and physical challenges, but even facial features that are called “dysmorphic features”, described as:

- A tubular shaped nose,

- Narrow palpebral fissures (a narrow opening between the eye-lids),

- Thin hair,

- Periorbital fullness (fullness around the eyes),

- Strabismus (eyes are not aligned properly: cross-eyed),

- Long fingers

- Hypertelorism (increased distance between eyes),

- A short philtrum (vertical piece of skin indentation between nose and upper lip)

- and an often present grimace.

We recognised my little brother in all of these other individuals with GAND. The younger kids looked exactly liked he did, back in the day. And a slightly older young man, 28 years of age, was so incredibly similar to him.

With tears in our eyes and goose bumps on our skin we started to bond with other parents and siblings over our experiences. Finding out about matching symptoms, developmental curves and even character traits! We could laugh together about typical quirks, and their love for peculiar games and objects. We could share solutions for everlasting challenges, such as brushing teeth and potty training.

You realise then what an early diagnosis could actually do for parents.

My parents had no idea about the typical characteristics of GAND, and as such had no specific way of preparing for a future or a targeted therapy for my brother. While they were in uncertainty for such a long time, they attempted everything within their ability to make sure my brother would have all the chances that he might need to grow.

When children don’t display the type of behaviour at a certain age that is expected, parents start looking for an explanation as to why: It might start at the way a baby makes social connection, the way they make eye-contact for instance. Early symptoms may be disregarded as it could be a phase they grow out of. Then a-typicalities may become more physical, for instance when a baby is not able to sit up straight, or to crawl. Perhaps it becomes really obvious when language skills do not develop at all. As soon as a developmental delay becomes noticeable, be it in physical or cognitive development, question marks arise.

Families with young children diagnosed with a disability can be informed about the cause, allowing them to prepare for a future. They can build a supportive network together with those in a similar situation; compare their kids’ behavior, talk about struggles and achievements, and about their developments in life. These families are the important ones to track the course of a genetic syndrome and its’ actual phenotype.

As the gene sequencing technologies have developed immensely, it has become much cheaper and faster to decode the essence of your genetic code. That is why not only we had the chance to receive a diagnosis, but many other families as well. Consequently, a whole lot of new syndromic genetic disorders have been classified. This also means that a lot of these syndromes remain just un-described gene-codes. Describing the behavioural and physical symptoms of a genetic syndrome is incredibly challenging. It requires a lot of effort and dedication. The clinical world is working hard to describe all the newfound genes, in order to support families with a new diagnosis.

In Otter Words: Knowing a causal mechanism of a disorder such as intellectual disability, and the fact that it’s syndromic, allows for us to understand a certain behaviour or limit of that individual. It may offer a sense of acceptance and relief. It may resolve the question of guilt. Finding others with the same genetic disorder with similar traits and symptoms, is a great help. As the real experts on the topic are family.

Wow! Wow! Wow! Thank U